Authored by Matt Taibbi via Racket News,

Nearly five months ago I was presented with a rare opportunity, to look through internal correspondence at Twitter. A small group of other journalists and writers soon jumped down the rabbit hole to join the one-in-a-million search.

At the time the company was just completing a contentious sale, which featured multiple stops, starts and legal actions, along with competing furious public relations campaigns. New owner Elon Musk accused the old regime of lying about the percentage of Monetizable Daily Active Users (mDAU) on the platform (i.e. how much on Twitter was real traffic and how much was spam), said he was “obviously overpaying,” and insisted he was an advocate of the right “to speak freely within the bounds of the law.”

I was amazed at this story’s coverage. From the Guardian last November: “Elon Musk’s Twitter is fast proving that free speech at all costs is a dangerous fantasy.” From the Washington Post: “Musk’s ‘free speech’ agenda dismantles safety work at Twitter, insiders say.” The Post story was about the “troubling” decision to re-instate the Babylon Bee, and numerous stories like it implied the world would end if this “‘free speech’ agenda” was imposed.

I didn’t have to know any of the particulars of the intramural Twitter dispute to think anyone who wanted to censor the Babylon Bee was crazy. To paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut, going to war against a satire site was like dressing up in a suit of armor to attack a hot fudge sundae.

This was an obvious moral panic and the very real consternation at papers like the Washington Post and sites like Slate over these issues seemed to offer the new owners of Twitter a huge opening. With critics this obnoxious, even a step in the direction of free speech values would likely win back audiences that saw the platform as a humorless garrison of authoritarian attitudes.This was the context under which I met Musk and the circle of adjutants who would become the go-betweens delivering the material that came to be known as the Twitter Files. I would have accepted such an invitation from Hannibal Lecter, but I actually liked Musk. His distaste for the blue-check thought police who’d spent more than a half-year working themselves into hysterics at the thought of him buying Twitter — which had become the private playground of entitled mainstream journalists — appeared rooted in more than just personal animus. He talked about wanting to restore transparency, but also seemed to think his purchase was funny, which I also did (spending $44 billion with a laugh as even a partial motive was hard not to admire).

Moreover the decision to release the company’s dirty laundry for the world to see was a potentially historic act. To this day I think he did something incredibly important by opening up these communications for the public.

Normally when someone comes to you with a story you ask what it is they want or expect out of press coverage, both so you can understand their motives and to avoid misunderstandings later on. I asked the question, but I can’t say I ever fully understood the answer. It didn’t matter. Within a few days of seeing documents it was clear we were looking at something bigger than us, Musk, or Twitter, more or less completely obviating the motivation question as far as I was concerned.

I went into the project expecting to answer a few narrow questions, maybe about how internal content moderation worked, or if federal law enforcement made an inappropriate call or two to discourage high-profile stories. Remember, in the pre-Twitter Files world, Twitter was still denying that it shadow-banned people at all (“We do not,” they’d explained). Also, the notion that there’d been any contact at all between the FBI and a company like Facebook ahead of the Hunter Biden laptop story was a national scandal after Mark Zuckerberg blurted out something along those lines to Joe Rogan. Just one possible recommendation made headlines, let alone regimes of spreadsheet requests.

When we got into the Files, we were caught off guard. The content-policing system was more elaborate and organized than any of us imagined. A communications highway had been built linking the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence with Twitter, Facebook, Google, and a slew of other platforms. Among other things this looked more like a cartel than a competitive media landscape, and I had an uneasy feeling early on that publicizing this arrangement might create a host of unanticipated problems for everyone involved. Still, there was no question this was in the public interest. So we kept going.

About two weeks into the #TwitterFiles project, the company suspended the accounts of CNN’s Donnie O’Sullivan, Ryan Mac of the New York Times, VOA’s Steve Herman, and a few other social media personalities like Aaron Rupar, reportedly for sharing information about the movement of Elon Musk’s private jet.

My phone instantly blew up with wisecracks. “I must have missed John Stuart Mill’s ‘private jet exception’ passage in On Liberty,” texted one ball-busting friend. After about six ringtones I rolled my eyes, popped an Advil, and turned my phone off, knowing what was coming. The suspensions, even if quickly reversed, were sure to ignite nuclear levels of pearl-clutching and self-pity among the same censorious power-worshipping media jerks who a few months before were howling about Musk because they thought he was for free speech.

Bari Weiss decided the situation demanded a public statement. I absolutely respected the decision, but disagreed. I thought the outcry — coming from people who never said a word across years of suppression of the type of people I wrote about in the “Meet the Censored” series, like J6 videographer Jon Farina, Canadian broadcaster Paul Jay, and the World Socialist Web Site — was a bad-faith trap. These people didn’t care about the issue at all, except in a self-interested way, while they probably did care about shifting public attention from #TwitterFiles releases.

From that moment the project was a football between two committed antagonists: a sporadically censorious CEO I didn’t really understand on one hand, and on the other, a bloc of vicious uniparty authoritarians who were committed to throttling speech as an ideological goal, whose methods and tendencies felt all too familiar.

The latter group isn’t interested in engagement and prefers a strategy of obliteration. This played out in a very real way for new Twitter from the start, in the form of sweeping advertiser boycotts led by groups like David Brock-founded Media Matters, Free Press, Accountable Tech and Color of Change. Twitter Files reporters like me experienced a less personally damaging version of the same deal, through an impressive total mainstream coverage blackout of #TwitterFiles revelations, coupled with a near-constant string of smears and stories assuring the uniparty faithful that all those documents they were assiduously kept from reading about were nothingburgers.

We were never on the same side as Musk exactly, but there was a clear confluence of interests rooted in the fact that the same institutional villains who wanted to suppress the info in the Files also wanted to bankrupt Musk. That’s what makes the developments of the last week so disappointing. There was a natural opening to push back on the worst actors with significant public support if Musk could hold it together and at least look like he was delivering on the implied promise to return Twitter to its “free speech wing of the free speech party” roots. Instead, he stepped into another optics Punji Trap, censoring the same Twitter Files reports that initially made him a transparency folk hero.

Even more bizarre, the triggering incident revolved around Substack, a relatively small company that’s nonetheless one of the few oases of independent media and free speech left in America. In my wildest imagination I couldn’t have scripted these developments, especially my own very involuntary role.

I first found out there was a problem between Twitter and Substack early last Friday, in the morning hours just after imploding under Mehdi Hasan’s Andrey Vyshinsky Jr. act on MSNBC. As that joyous experience included scenes of me refusing on camera to perform on-demand ritual criticism of Elon Musk, I first thought I was being pranked by news of Substack URLs being suppressed by him. “No way,” I thought, but other Substack writers insisted it was true: their articles were indeed being labeled, and likes and retweets of Substack pages were being prohibited.

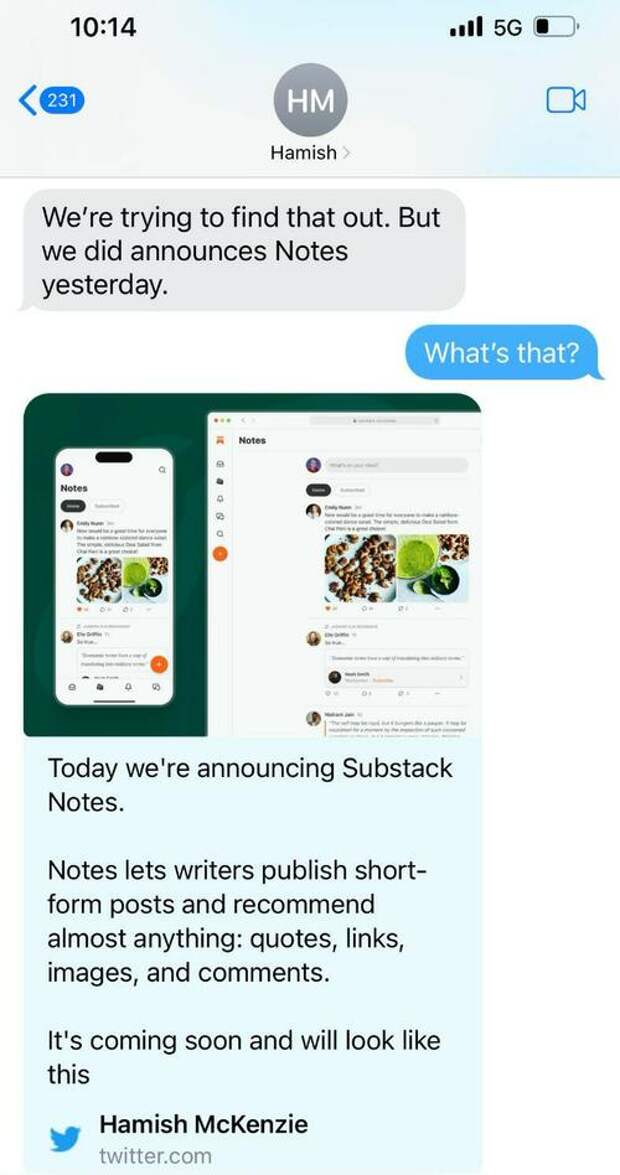

I asked Substack co-head Hamish McKenzie what was going on. He said he wasn’t sure, but offered that they’d just announced a new “Notes program” the day before. I had to ask, “What’s that?” I had no clue what ‘Substack Notes” was:

As many unfortunately know now, my next move was to ask Elon what was going on. He didn’t answer right away, which is fine, the man is busy, but the math on this was pretty simple. Whatever was going on between Twitter and Substack had nothing to do with me or with other Substack writers, and if Twitter was going to label our work unsafe and not allow us to share my articles, I couldn’t endorse all this by using the platform, and said so. This prompted a quick ping! and a furious Signal question: “So you want Substack to kill Twitter?”

Subscribers to Racket News can read the rest here...

Свежие комментарии