With the end of the fiscal and calendar year upon us, sellside research rushes to put to print its latest forecasts about the coming year, and HSBC - which recently made headlines when it slashed its 2016 year-end forecast on 10-Year yields from 2.8% to 1.5% - is no exception.

Earlier today, the firm's research team issued a report laying out the top 10 risks for 2016, which had a peculiar caveat suggesting some at the bank is not in a rush to get arrested.

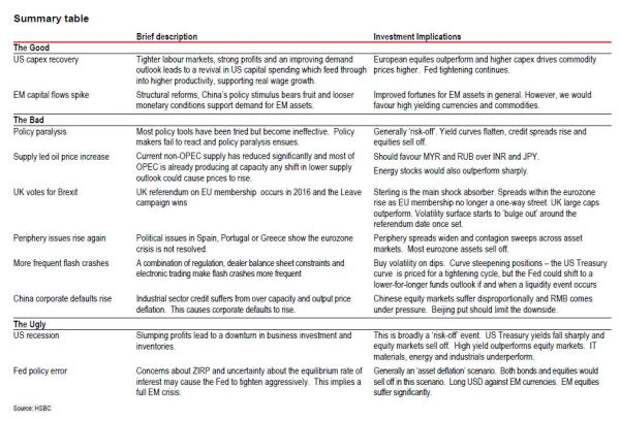

..... in which it laid out what it believes are the 2 "good" risks to the economy - a US capex recovery and a return to EM capital inflows - as well as the 6 "bad" risks such as policy paralysis, supply-led oil price increase, a UK vote for Brexit, political crises in Europe's periphery, more frequent flash crashes, and an increase in China's corporate defaults, as well as HSBC's two "ugly" tail-risks: a US recession and Fed policy error.

We will focus on the negative ones. This is how HSBC prefaces its risk packet:

The “bad” category dominates, filling six of the 10 slots. This is not because we are particularly gloomy; on the contrary, our base case is for continued slow growth in 2016. But “bad” risks often have a more immediate impact than “good” ones, and our focus here is on 2016. Indeed, upside risks tend to be gradual in nature. Global trade agreements such as the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) or the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and technological improvements should add to global growth beyond next year. It is rare that a growth positive shock surprises markets.

We don’t want to cry wolf about any of these risks. But in a world that remains highly leveraged and with limited policy ammunition to offset any new downturn, markets will be sensitive to any shift in consensus. The global economy and markets are more exposed to downside risks today than they would have been if the expansion had been more robust, or we were earlier in the global business cycle.

With that caveat, here are the key downside risks:

1. Policy paralysis

Policymakers appear to run out of policy options, or are either unwilling or unable to adopt new policy to stimulate growth

Policymakers may wish to try something else to stimulate growth but what happens when there are no obvious viable options? A number of unconventional and conventional policies have been tried in recent years, all with the objective of boosting nominal GDP. Quantitative easing, negative rates and fiscal policy have been put in place. Helicopter money is for now just a theoretical concept but it could be tested.

What happens when policies appear not to work? Between lurching from one type of policy to another or when absolutely everything appears to have been tried, perceptions of policy paralysis may set in. This may be a direct consequence of the lack of ability or willingness to try something new at a time when existing policies are not effective. Policymakers are seen as impotent, either unable or unwilling to take the bold steps necessary.

In the Eurozone this might apply to the ECB if it reaches the outer limits of what is technically and legally feasible, whilst governments fail to forge ahead with the necessary integration and supply-side reform. It is already controversial that the ECB is expanding its balance sheet and paying a negative rate on deposits. We wonder how much further the ECB can go before exhaustion (see our report Quantitative Exhaustion, 4 November 2015) is followed by policy paralysis.

Faced with another downturn, just as the US presidential election approaches, it is hardly the right time for the US to unleash fiscal loosening, especially given the starting point for debt levels. And it is difficult to imagine the Fed starting QE4. The US could be much closer to the policy buffers than central bankers and politicians would care to admit.

Investment implications

- Flatter yield curves

- Wider credit spreads

- Equities suffer – particularly in EM

2. Supply-Led Oil Price Increase

Oversupply should fall and low spare capacity in OPEC offers limited buffers to supply disruptions, meaning oil could move sharply higher

Following the 60% drop in crude prices since mid-2014, the market seems to be fixated on the risk of further falls. This is understandable given a backdrop of firm supply pressure from OPEC, large inventory overhangs and the potential for increased Iranian exports next year. However, we believe investors should be increasingly concerned about the risks of a sharp move higher in crude prices. Not only should the extent of oversupply fall dramatically in 2016, but low spare capacity within OPEC means that buffers against unexpected supply disruptions are very limited. Moreover, if OPEC abandons its policy and reduces output, prices could well rally considerably. As far as tail risks go, they seem skewed firmly to the upside, in our view.

Producers outside OPEC have responded much more quickly to lower oil prices than the market was expecting. The most striking evidence of this is the relentless series of downgrades to non-OPEC supply growth estimates. Looking at the monthly evolution of the US Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) forecasts, 2016 non-OPEC supply growth was seen at 0.8mbd in February. Just nine months later, the forecast points to a y-o-y decline of 0.3mbd. The International Energy Agency (IEA) sees an even larger fall of 0.6mbd, which would be the largest annual decline in non-OPEC output since 1992 (when the collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in a 1mbd contraction). According to the IEA, non-OPEC volumes grew 2.5mbd as recently as 2014.

The biggest supply response thus far has come from US tight oil production, which has a much shorter production cycle than conventional oil extraction. The US onshore rig count has fallen sharply by 66% since the peak in Q4 2014, and the full effects of this have only recently started to translate into falling production. On our estimates, liquids output from the main US onshore plays should fall around 650kbd y/y in 2016. However, it’s important to remember that US tight oil only accounts for around 5mbd out of total non-OPEC supply of nearly 60mbd. Large project deferrals and cancellations will only impact supply some years down the line, but decline rates from existing production are likely to rise in the near term as the industry cuts back on maintenance capex such as infill drilling.

While this risk would present a drag to global growth it would be beneficial for a number of oil producing nations. As such, the investment implications are quite clear. Firstly, markets will be looking for direct oil exposure. This should lead MYR and RUB to appreciate and IND and JPY to depreciate. The global equity energy sector is also likely to be well bid. In particular, we believe the Russian market should rally. Furthermore, oil services companies should outperform the majors in the integrated sector. USD high yield debt is also likely to benefit due to diminished credit risks in the shale oil sector which makes up roughly 15% of the market. In addition, any concerns about GCC currency pegs are likely to evaporate; hence, 5-year Saudi Arabian CDS should come down from today’s elevated level. We would also expect US high yield to be of particular interest. Spreads in the USD high yield energy sector would tighten significantly.

Investment implications

- Positive for USD high yield debt markets and oil exporter currencies

- Saudi Arabia 5-year CDS should come down

- Saudi and Russian equity markets rally most

3. UK votes for Brexit

Repercussions would be felt across Europe but terms of the exit would be key

David Cameron, the UK prime minister, has promised that by the end of 2017 at the latest there will be a referendum on whether the UK should remain in the European Union. But it is clear he would like to hold the vote in 2016, if at all possible, not least to reduce the uncertainty the event will engender.

There would be significant uncertainty in the immediate aftermath of a “leave” vote. The UK cannot negotiate the terms of its exit on a hypothetical basis, so there would be no clarity on what the post-EU arrangement would look like. If the UK remained a member of the European Economic Area, alongside countries such as Norway and Iceland, the economic implications would be very different to those of a complete withdrawal.

The UK's transition to non-EU member status could take up to two years, at which point its membership would end automatically, if no agreement has been ratified by the European Council. The longer the period of uncertainty, the greater the likely impact on investment and growth. Untangling European laws and replacing them with domestic legislation could be a very long process, requiring government resources to be diverted from other areas of policymaking.

Also, the future of the UK itself could once again be called into question. If the regional breakdown of the referendum voting showed a majority of Scottish people had voted to stay in the EU, calls for a second Scottish independence referendum would intensify.

If there is a “leave” vote, it is highly likely that the UK would seek to preserve the extensive and mutually advantageous goods trade between it and the other EU members. The impact on services trade, which is very important to the UK, is harder to call. For example, some financial services may opt to leave the UK in order to retain full access to EU markets. Depending on the exit agreement, migration flows could be restricted which could reduce the labour supply and risk a loss of competitiveness.

From the EU's perspective, a UK exit would send out the message that EU membership is not a one-way street, raising concerns about other potential withdrawals and denting investor confidence across the region. If the UK were to impose restrictions on migration, it would also be negative for countries that benefit from employment opportunities for their citizens and remittances from the UK.

Investment implications

- GBP would sell off…

- This would shelter the FTSE 100 given the large share of overseas revenues

- The possibility of contagion could put peripheral rates under pressure

4. Periphery issues rise again

2016 is shaping up to be an important year from a political perspective in the eurozone periphery:

- After the inconclusive elections on 4 October, the leader of the Portuguese Socialist Party Antonio Costa was officially named Prime Minister on 26 November, securing the support of other left-wing parties for his minority government. However, the government faces many challenges ahead. This will start with the approval of the 2016 budget – which will then have to go under the scrutiny of the European Commission – as the parties supporting the government have been arguing for a relaxation of austerity and a U-turn on key reforms in the labour market and on pensions (see our report Portugal’s new government: Are markets right to be relaxed, 27 November 2015)

- Spain also has general elections on 20 December, with an increasingly fragmented electorate. The latest polls show a close race between the ruling Partido Popular, socialist PSOE and reformist Ciudadanos, with leftist radical Podemos a more distant fourth. The electoral law complicates things, but in a nutshell it is unlikely any party will obtain an absolute majority and even a two-party coalition might fall short. This could result in delays before a government can be formed and prolonged uncertainty. Meanwhile, the pro-independence platform of parties that won the Catalonia election on 27 September has formally started the process towards declaring independence – defying a ruling by the Spanish constitutional court – and uncertainty could continue well beyond 20 December (see our report Notes from Madrid, signs of economic rebalancing, political uncertainty dominates, 5 November 2015)

- In Greece, progress on the implementation of the third programme of financial assistance of up to EUR86bn agreed in August has been slow. Further delays can be expected in the first programme review – due to start in the coming weeks – which will tackle politically-sensitive issues such as pension reform and privatisations. Debt relief, which is the key precondition for the IMF to be on board, will only be discussed on completion of the review. The prospect of a successful review completion is also a condition for the ECB to accept Greek bonds as collateral in its refinancing operations, and buy them under QE (see our report Greece and its creditors: Today’s deal is just the first step, expect delays in negotiations, 19 November 2015)

So far, the ECB QE programme has helped contain the market reaction to some of the political uncertainty that has been building up in these countries, even if we have seen a widening of the spreads in the sovereign bonds space, for example compared to Italy which is experiencing a period of relative political stability. Yet, there is the potential for things to go wrong, and if this was the case, even an expansion of the ECB QE programme might not be enough to avoid a further widening of spreads, renewed escalation of the eurozone sovereign crisis and fears of a possible exit by a country from the union. Such a scenario could be triggered by a combination of the following events:

- In Portugal, the new government puts forward a very expansionary 2016 budget, which is rejected by Brussels. This simultaneously triggers a downgrade by the DBRS agency, making Portuguese debt ineligible for QE and no longer accepted as collateral in the ECB refinancing operations, leading to a spike in spreads and rising concerns for the banking sector. The government loses the support of the radical left-wing parties and elections are called for the end-April 2016 – the earliest they can be called – and the prolonged period of political uncertainty starts weighing on the already weak economic recovery

- Inconclusive elections in Spain, with parties unable to form a governing coalition, lead to a prolonged period of uncertainty. The country is unable to pass a revised 2016 budget as requested by the European Commission to meet EU fiscal targets and therefore Brussels formally starts a procedure to sanction the Spanish government. Meanwhile, the escalation of tensions between Catalonia and Madrid on the issue of independence starts to hit consumer and investor confidence – Catalonia accounts for almost 20% of Spanish GDP – leading to a marked slowdown in the economy, which together with the fiscal slippages and rising debt triggers a rating downgrade. As a result, the spread widens significantly

- Greek negotiations with its creditors, including on debt relief, prove difficult as the continuous delays end up harming the level of trust between the parties. Syriza MPs split on the issues of pension reform and privatisations and the government – already relying on a thin majority by only three MPs in the 300-seat parliament – loses its majority. Opposition parties decide not to support the government in passing the necessary reforms, which leads to a stall in the programme negotiations and new elections being called, amid rising fears of a possible Grexit in the markets

The potential for one or more country to leave the Eurozone and the net effect on peripheral (and other) asset markets has been hotly debated since the Eurozone crisis of 2011. The potential for erratic cross border capital flows and contagion across the periphery, and potentially core countries, are the most feared outcomes of a Eurozone break up or country exit scenario.

Investment implications

- Periphery spreads widen and Bunds enjoy safe-haven flows

- European equities fall

- EUR sells off

5. More frequent flash crashes

What if a combination of regulation, dealer balance sheet constraints and electronic trading leads to further declines in liquidity?

On many days, the markets function well, with investors and dealers able to buy and sell what they want to without significantly moving prices. But, on some days, a market nearly stops functioning – and prices can swing dramatically, impact the value of assets significantly, and make it difficult to buy or sell. This was seen in the October 2014 US Treasury market flash crash and the August 2015 equity flash crash.

We see two main reasons for the changes in market behaviour. First is the shift from human to automated trading. Second is the reduction in the size of dealer balance sheets, a reflection of shifts in financial regulations introduced after the 2008 financial crisis. Dealer balance sheet size has fallen by 40% from its peak to June 2015 and repurchase agreements fell by over 50%.

Historically, dealers had incentives to moderate market reactions to flows and thus maintain profitable relationships with their customers. The market structure meant that dealers often had better flow information than customers, which facilitated liquidity. Changes in market structure, such as the widespread use of automated trading, and higher costs of maintaining large balance sheets on the back of regulatory changes, have, in some cases, changed the market reaction to flows. There are now fewer incentives for dealers to step in and moderate market reactions to flows and, in some cases, dealers do not have as much information about flows as before.

We expect the impact of these shifts to continue to be felt. What is unclear is just how much market trading patterns and liquidity in recent decades will change, or whether the way assets are priced will be affected on a temporary or even permanent basis.

Until recently, the impact of reduced liquidity has been most visible in short-term “flash crash” events. However, the effects could be longer term. For example, the higher cost of maintaining large balance sheet seems to be causing a shift in the pricing of US interest rate swaps. The swap spread, representing short-term bank borrowing costs, is negative from five- to 30-year maturities. Financial theory suggests this spread inversion should only occur if the banking system was less risky than US Treasury securities. This is clearly not the case, as seen by the positive spread in the corporate bond market for financial credits. In our view, the swap spread shifts are best explained by the high cost of balance sheet for US banks and dealers. If this is a long-term change in market structure, then spread shift may be long term as well, with implications for asset values and investment strategies going forward.

Less liquidity may affect the structure of markets over time. The shift to lower yields and more competitive bond markets since the 1980s illustrates this. The number of primary Treasury dealers fell by half as the bid-to-offer spread narrowed and yields fell. There was even more consolidation in the buy side of the bond market as market liquidity encouraged consolidation.

With automated trading, the bid-to-offer spread will likely remain narrow in the most liquid markets. Potential market effects from this, combined with smaller balance sheets, are:

- Further drops in market liquidity to reflect the risk of a flash crash on dealer capital and investor performance

- Increased buy-side focus on capacity constraints in an uncertain liquidity environment. This favours a trend towards a more boutique style trading set-up, even within larger firms

- Trading activity migrating to less constrained venues and a further reduction in the liquidity of the most-affected areas

- Wider bid-to-offer spreads in less automated markets to reflect the true liquidity risk or an increase in the market impact of trades in all markets

Investment implications

- Buy volatility on dips

- Bonds tend to outperform equities in these events

- 2-year US Treasury yield should drop

6. China corporate defaults rise

Credit stress is rising especially amongst industrial sectors that suffer from overcapacity and output price deflation

2016 will see a continued rise in credit stress especially amongst the traditional industrial players, led by State-Owned-Enterprises (SOEs). There is a risk that a rise in defaults amongst these issuers has the potential to have wider implications.

Identifying the fragile issuers

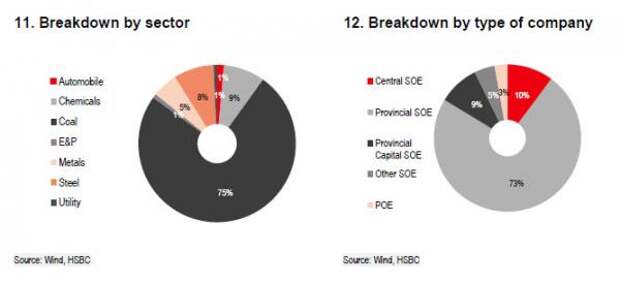

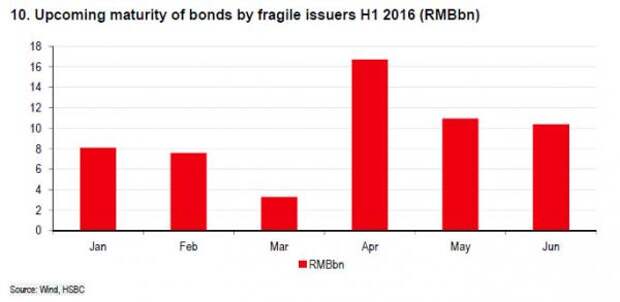

We conducted credit tests on the universe of onshore Chinese credit bonds maturing within H1 2016. Based on a combination of liquidity, earnings and debt coverage criteria, we identified 30 issuers (with 43 bonds outstanding) that we think are vulnerable to potential debt servicing issues in H1 2016. Without external intervention or support, we think these issuers are particularly fragile against refinancing risks and may face potential creditor actions (especially banks) if financial profiles weaken further.

By maturity breakdown, the first half of next year is particularly heavy in vulnerable bonds coming due, with nearly 30% (or RMB16.7bn) concentrated in April alone (Chart 10).

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of the vulnerable issuers/bonds fall in the coal mining (75% by bond notional), chemicals (9%) or steel (8%) sectors (Chart 11). In terms of company types, the risk group is dominated by provincial-level SOEs (73% by bond notional), followed by Central SOEs (Chart 12). POEs have the lowest percentage in our fragile list, probably due to a biased selection effect of onshore capital markets. These conclusions are consistent with our findings highlighted in our report China Onshore Monthly: Look out for a correction, 4 November 2015, where we screen for the weaker links in a bigger universe.

Given, however, that borrowers are heavily concentrated at the provincial level of local government (there are 33 of them, see Chart 12), Beijing should have quite strong direct control over potential defaults. So, whilst we believe a credit-led risk scenario is a significant tail risk, it is a low likelihood event, to which we attribute a less than 5% probability.

Clearly, a deterioration of the Chinese credit environment would have a significant impact on Chinese assets. As SOEs would have the support of the central government it is fairly likely that the private sector would suffer more and earlier than the state-owned sector. From that perspective, it is likely that Chinese equity markets would suffer most. That said, dim sum markets would also face significant selling pressure.

Investment implications

- Chinese equities and dim sum bonds directly impacted

- Policy action from Beijing limits downside risks

- Global assets would be exposed towards any CNY weakness

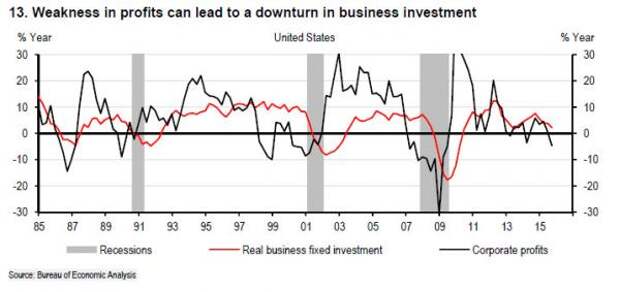

7. US recession

Slumping profits leads to downturn in business investment

A protracted slump in profitability can make companies more uncertain about the future and often leads to a downturn in business investment spending. Once the contraction in investment is severe enough, a recession is usually the result.

Continued strength in the US dollar is one factor that might pressure corporate profits, reducing export demand and boosting import competition. Sluggish global growth would exacerbate the drag from net exports.

A drop in the stock market as profits disappoint would impact business and consumer sentiment and further restrain spending. Even if interest rates were to hold steady or decline, businesses would still refrain from making new investments due to a lack of confidence in final demand.

A full-fledged recession would involve firms making cutbacks in their workforces in addition to reductions in capital expenditures. Accelerating layoffs would lead to a drop in personal incomes and additional weakness in household spending.

Corporate profits as measured in the national accounts have slumped in the past year, and real growth in business fixed investment has been sluggish. A US recession is a possible risk in 2016 if growth in profits does not improve.

A sharp slowdown in US growth leading to a recession is likely to precipitate a broad “risk off” move. We believe the main beneficiaries of this shift would be the US dollar and Treasuries. A strong USD could thus be both the cause and the effect of a US recession, with dollar strength first driving a reduction in corporate profits and then benefiting from safe-haven flows in the ensuing downturn. These flows should also drive 10-year US Treasury yields lowers. The HSBC Fixed Income Strategy sees 10-year yields falling to 1.5%. But, a US recession should push yields even lower.

Equity markets are likely to sell-off fairly sharply as weakness in the US economy is exacerbated by sluggish global growth. Perhaps counterintuitively though, we would expect the relative safe-haven status of US equities to mean that it outperforms the wider equity market, with emerging-market equities likely to be the hardest hit. Within the US, we believe the sectors which are mostly dependent on exports would suffer given further USD strength. As such, we would expect IT, materials, energy and industrials to be the biggest underperformers.

Investment implications

- Broad “risk off” move, with USD and US Treasuries rallying

- IT, materials, energy and industrials equity sectors likely to suffer

- Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Turkey and Mexico would be the big losers in EM

8. Fed policy error

An uptick in inflation could convince the Fed to speed up its pace of tightening, which could act as a drag on economic activity

In September, the median FOMC policymaker projected a rise in the federal funds rate to nearly 1.5% at the end of 2016 and to over 2.5% at the end of 2017. The real federal funds rate, according to the FOMC's projections for core inflation, would rise from around -1.0% currently up to 0.7% at the end of 2017.

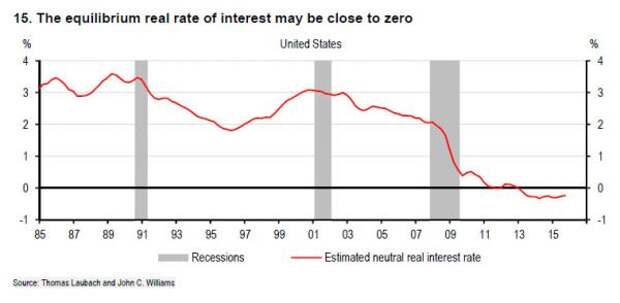

There is a risk that following this path of rate increases could slow the growth of aggregate demand in the economy by more than anticipated. The equilibrium real rate of interest appears to have declined compared to the past and may not rise very much in the near future if labour force and productivity growth remain low.

Uncertainty about the equilibrium rate of interest may lead Fed policymakers to react even more strongly to actual inflation outcomes than would otherwise be the case. Any uptick in core inflation could convince the FOMC to speed up its pace of policy tightening.

In this scenario, the lagged effects of monetary tightening could end up slowing economic activity more rapidly than expected, leading to a stop-and-go policy and increased volatility in financial markets.

Emerging markets investors have adapted to the idea of Fed lift-off at the end of this year and have moved to focus on the pace and duration of tightening. The overwhelming consensus in the market is that the Fed will revise down its dot-plot towards lower market expectations, as it has repeatedly done so throughout 2015. The improvement in EM risk appetite since October, following a dismal third quarter, rests on the idea that this is going to be the most ‘dovish’ tightening cycle ever with potential long pauses, even reversals of the hike(s).

In our recent report, our base-case entails near zero US real interest rates on 10-Y Treasury for 2016, which, everything else held constant, gives us stable non-resident capital flow at around 2015 level of 1.8% of GDP, or nearly USD500bn. If we were to increase US real interest rate assumption to slightly over 1.0%, this would nearly halve EM capital flows to around USD280bn or c1.2% of GDP, the slowest capital flow since 1990. Assuming the same extent of capital outflows by residents (such as external asset acquisition and external debt repayments), this might give even deeper net negative capital flows (net of resident and non-residents).

This scenario is problematic for most assets. The key theme of the market would be one of asset depreciation – where most assets would sell off. This sets this risk apart from other ‘Risk-Off’ events as the impact would be felt in both equity and bond markets. Given that market returns have predominantly been driven by valuation expansions since the great recession this presents most markets with fairly large downside risks. Bond markets would struggle initially which would raise discount rates and make current equity market valuations unsustainable.

Investment implications

- General ‘asset deflation’ scenario. Both bonds and equities sell off.

- US dollar likely to strengthen as EM currencies and assets sell off materially

- Assets in Brazil, Colombia, South Africa, Mexico and Turkey would suffer disproportionally